How Radio Stations Delivered Printed Newspapers in the 1930s.

For most folks, the Great Depression conjures up images of soup kitchens, "Will Work for Food" signs, and city streets filled with throngs of unemployed men. However, the Depression years weren't all gloom and doom. While business and finance ground to a halt, technology was booming. In terms of new applications and demand, technology experienced almost unceasing growth throughout the 1930s.

As the decade progressed, electricity extended into rural areas. Automobiles became faster, safer, and more luxurious. Aviation records were broken as quickly as they were set. Advances in medicine, entertainment, and labor-saving appliances were announced almost daily, and two worlds' fairs showcased the marvels of technology to come.

Radio was the star of technology, and the growth industry of the 1930s, largely because it touched the lives of nearly everyone. So, as more powerful transmitters were built, more reliable receivers poured from the factories. Deco style came to radio cabinets, and phonographs found their way into them as manufacturers vied with one another to capture the marketplace. Novelties such as radio broadcasts from airplanes and radio receivers in automobiles quickly became the norm. Radio was not welcome in all corners, however. Newspapers found radio a definite threat. It competed for advertising dollars, and lured people away from reading newspapers. (Why pay a nickel for a paper, when you could listen to the news for free?) The wire services that supplied newspapers with news and photos refused to allow broadcasters access to their services. The one news service that was formed to supply radio stations with news — the Transradio News Service — was the object of lawsuits by the conventional news services almost before it started business. (Perhaps ironically, some of the largest newspapers were either buying or establishing radio stations.)

Despite this enmity, there were people who hoped to bridge a gap between radio and newspapers. One such person was an engineer named William G.H. Finch. His company — Finch Telecommunications Laboratories — had developed a simple and low-cost system for transmitting and receiving facsimile (now known as FAX) by radio. He applied for his first patent in 1935.

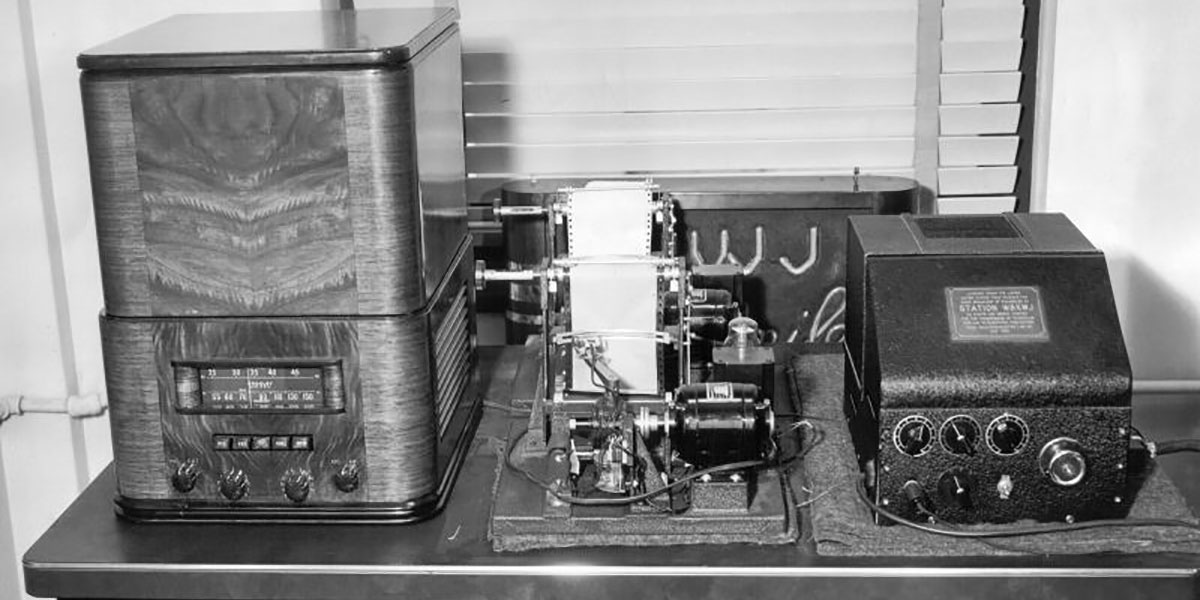

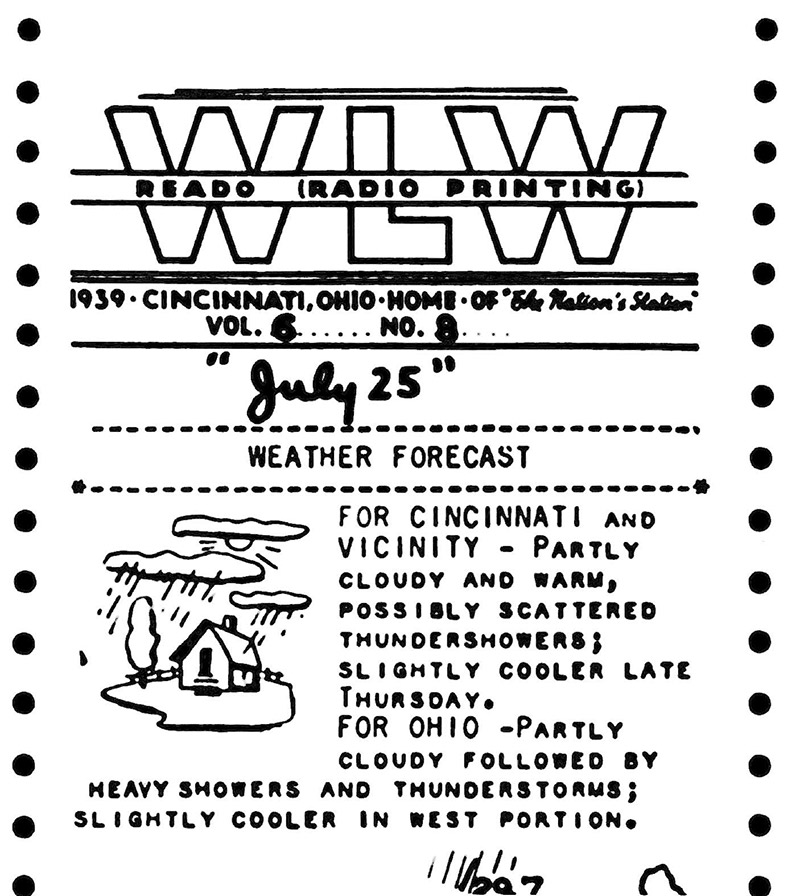

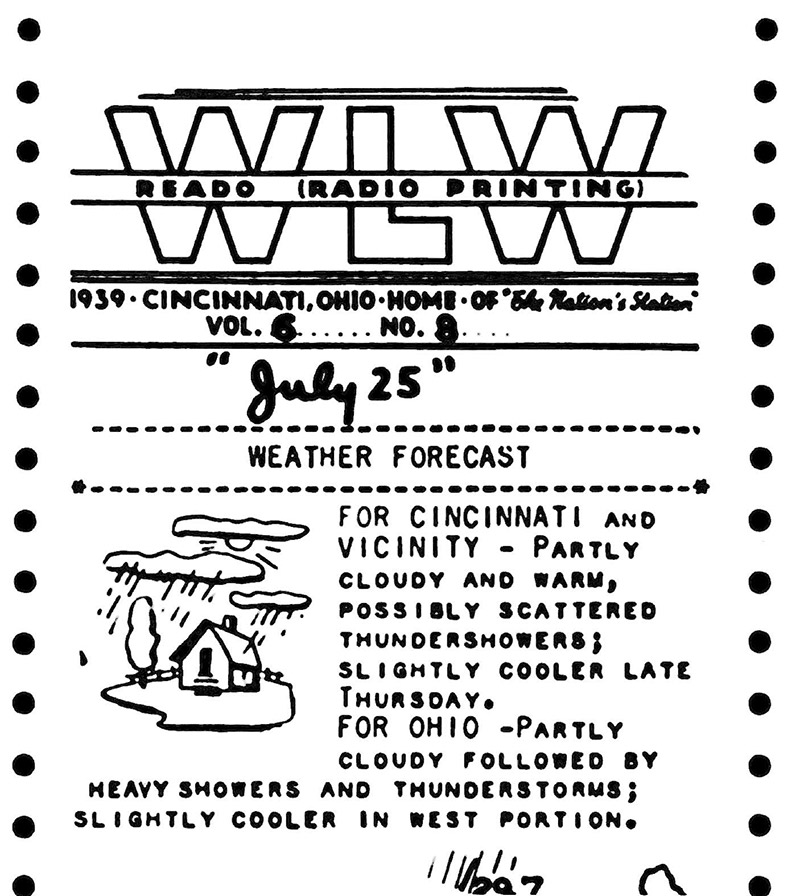

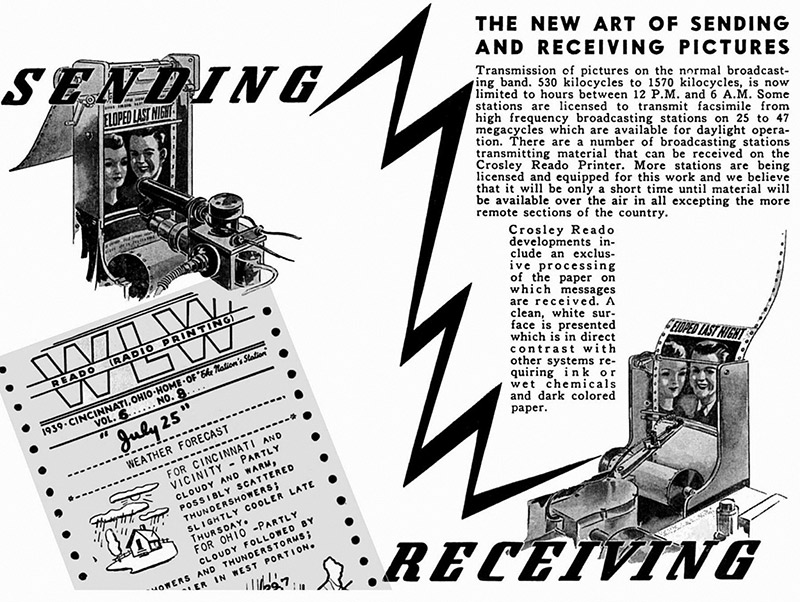

FIGURE 1. To save space, radio-printed newspapers used simple text and graphics. The print quality was acceptable, although the thermal and carbon printing processes left smudges.

Radio facsimile was nothing new. The first radio facsimile system was patented in 1905, and its earliest application was transmitting weather maps and other data to ships at sea (a practice that continues today). By the early 1920s, news services were transmitting photos by radio facsimile (the first wirephotos). Between 1926 and 1932, RCA established radio facsimile service via shortwave between New York and London, San Francisco, Berlin, and Buenos Aires.

In theory, radio facsimile transmission involved little more than substituting a radio carrier wave for telephone wires. But the reality was not that simple. Transmitters and receivers were complicated and temperamental, and usually required trained operators. Until Finch's system, radio facsimile equipment was just too complex and costly for most commercial applications.

Finch had three rivals: RCA, General Electric, and Western Electric, each a corporate giant that might have crushed him. But as a 1937 article in Business Week put it, the Finch system was "... the first to come out of the laboratory and into family parlors."

RCA had begun negotiations for online versions of four New York newspapers (The New York Times, Herald Tribune, American, and World-Telegram) in 1935. But even though experiments were made over the ensuing two years, no system was in place. Finch, on the other hand, had sold three US radio stations on testing his "radio printer" system by the end of 1937: WGH in Newport News, VA; WHO in Des Moines, IA; and KSTP of St. Paul, MN. The broadcasters received FCC permission to transmit radio facsimile signals in September of 1937, and the first transmissions of "radio-printed" news were made by KSTP the week of October 15, 1937. In November, the Iowa and Virginia stations were also broadcasting radio-printed news.

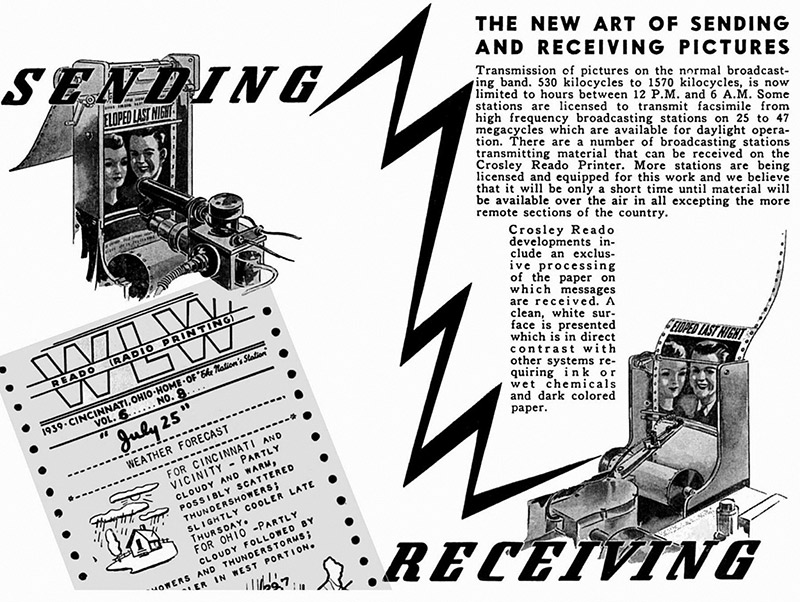

FIGURE 2. Efforts were made to educate the potential customer about radio facsimile, but without getting overly technical.

The typical radio facsimile unit was housed in what appeared to be (and usually was) a large radio or phonograph cabinet, with the radio receiver and printer housed as one unit within. The systems printed the news on a five-inch wide strip of paper that was either carbon-backed or heat-sensitive. Carbon-backed paper was backed up by a second layer of paper, on which images were made when a stylus touched the first layer. Heat-sensitive paper was similar to that used by 1970s printing calculators and FAX machines. The chemical treatment required for the latter gave the paper a gray or green tint. And the carbon-backed paper was a bit messy, but the quality was acceptable. Text and images were printed in black or dark gray in two columns. Photos and half-tone artwork didn't come through as well as in regular newspapers, but line art reproduced nicely.

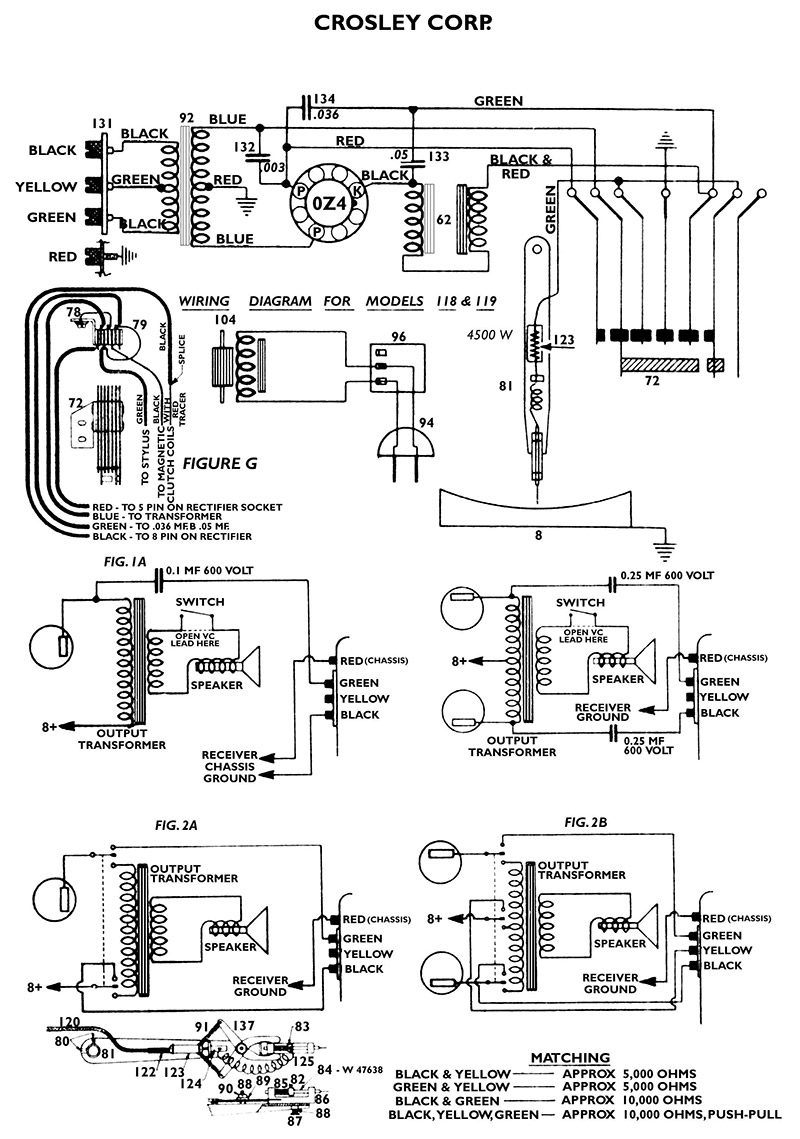

In operation, the scanning end of a radio facsimile transmission involved a moving photocell passing over text and image to be scanned. Electrical signals from the photocell varied with the darkness or lightness of a given spot on the paper being scanned. A carrier wave was modulated with these signals, and the signal broadcast on an agreed-upon frequency. The typical range was 25 to 50 miles, although some experiments were successful at ranges of several hundred miles — though not consistently.

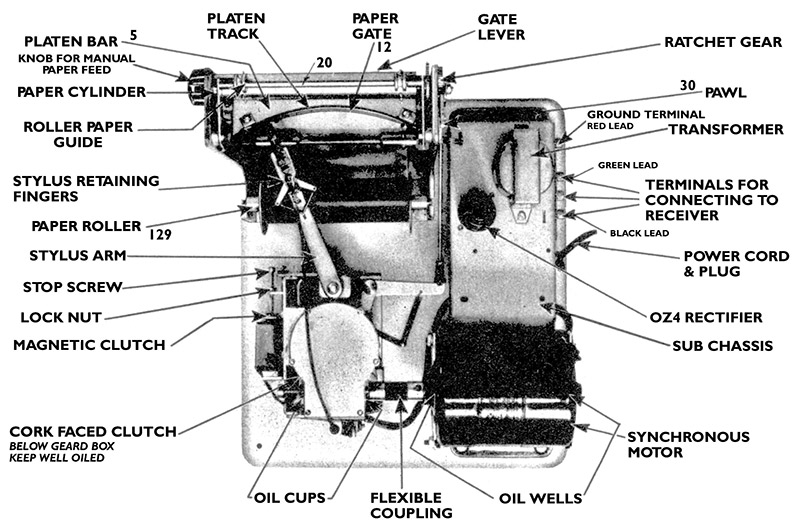

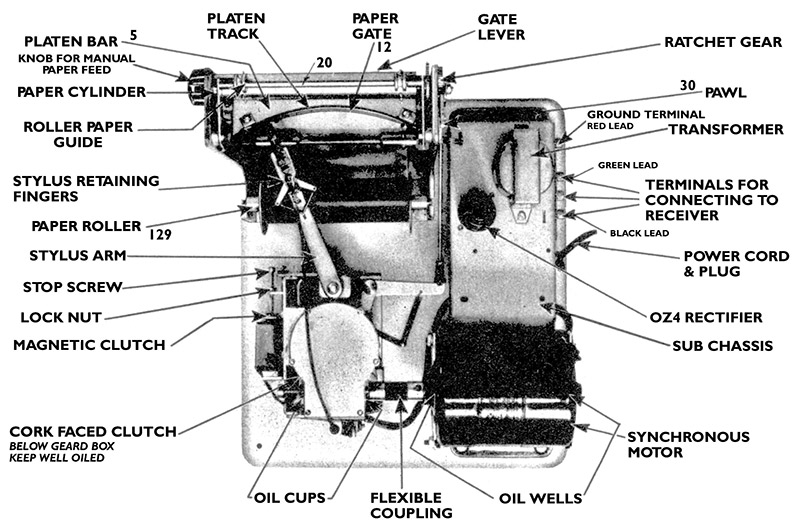

At the receiving end, the radio signals were converted to electrical impulses. A stepper motor on the printer moved a roll of paper 1/100-inch at a time, after which a stylus would glide across the paper's surface. When the stylus' driving mechanism received an electrical impulse (echoing what had been scanned), it pressed against the heat-sensitive or carbon-backed paper, leaving a black line. With this system, small dots or long lines could be placed on each line of the scrolling paper, and an image would gradually be built up, 1/100-inch at a time.

FIGURE 3. Detailed view of the printing mechanism from the Crosley Reado radio printer.

Participating broadcasters underwrote the entire effort as an experiment. Each radio station that signed on with Finch Laboratories placed 50 receiving sets in its broadcast area at a cost of $125.00 a piece — an investment of over $6,000.00 — the equivalent of nearly $200,000.00 today. And that didn't include scanning equipment and transmitter hook-ups. But broadcasters were optimistic, figuring revenue from advertising and subscriptions would justify the cost.

There were a few technical problems — the main ones being keeping the printer synchronized (minor), and static (major). As it turned out, facsimile broadcasts were not as "tolerant" of static as voice broadcasts. A burst of static lasting no more than a fraction of a second could wipe out several pages of a broadcast. Engineers were confident the problem could be solved, though.

By February of 1938, the Mutual Network stations (WOR in New York, WLW in Cincinnati, and WGN in Chicago) were conducting experiments with Finch equipment. Before long, their owners signed on to the program. WHK in Cleveland, Nashville's WSM, and California radio stations KMJ and KFBK of Fresno and Sacramento soon followed.

The FCC permitted stations to broadcast printed news between midnight and 6:00 am. At the time, radio stations routinely ended their broadcasts and signed off the air at 11:00 pm or midnight, so the time slot was ideal for delivering printed news before most people awoke. Stations at first used their assigned frequencies to broadcast the facsimile newspapers, but later changed or planned to change to high-frequency transmitters. Thus, WLW conducted experiments at 700 kilocycles, but planned to switch to 20,000 kilocycles for regular facsimile broadcasts. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch inaugurated its radio-printed version using its own experimental station — W9XZY — broadcasting at 31,600 kilocycles.

Once the receiving sets were in place, the cost to consumers was nominal. Rolls of heat-sensitive paper cost $1.00 each, and the estimated cost of the paper used in a week would be $0.10. (Paper consumption was projected to be about five feet per hour of transmission.) The cost of electrical usage in the average home would be increased by only $0.20 per week.

Most stations worked with local newspapers to provide the radio-printed news. (The exceptions were WHO and WGN, which used Transradio News Service as their news source.) Advertising sales would, of course, generate profits for all.

As enthusiasm grew, two radio manufacturers moved in for a share. RCA had experimented with radio facsimile messaging several years earlier, and lost little time getting back on the bandwagon with the manufacture of radio facsimile receivers. Crosley Radio Corporation, which was heavily committed on the broadcast end through its ownership of WLW, went a step farther. Its owner, Powel Crosley, Jr., licensed the Finch patents and started building a low-cost version of the Finch receiver. By January 1939, the Crosley factory had manufactured 500 sets, and set up an assembly line capable of turning out 100 sets a day. He dubbed the receivers and the service "Reado."

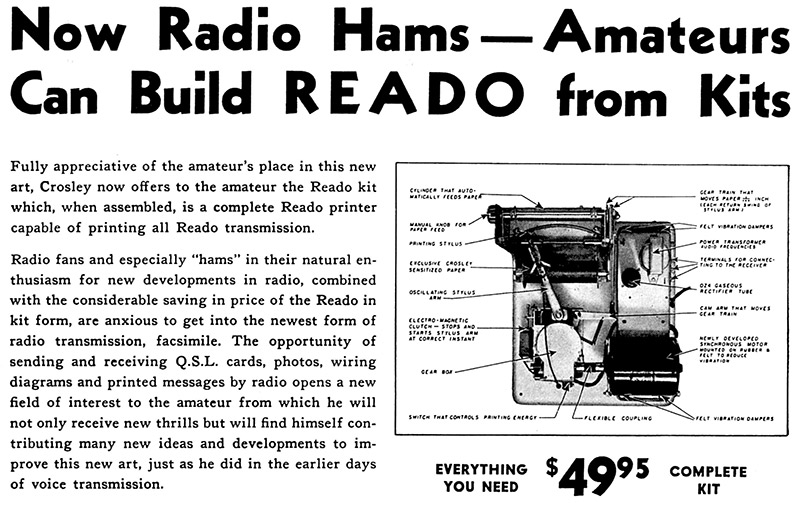

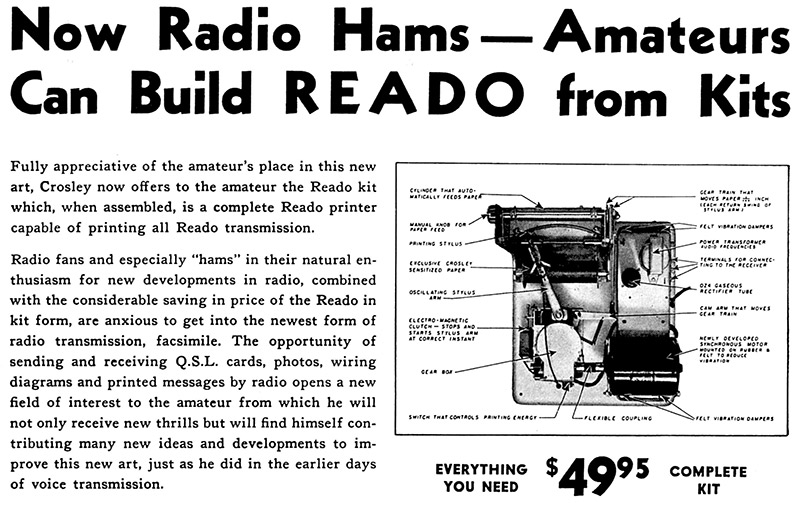

FIGURE 4. It was hoped that radio facsimile would have special appeal for radio amateurs, who were always seeking new projects.

These moves by Crosley, whose inexpensive radio sets were, in large part, responsible for the immense popularity and growth of radio from 1921 on, were a huge vote of confidence for radio-printed news. In industry circles it was taken for granted that, if Powel Crosley, Jr., the man the press had dubbed "the Henry Ford of Radio," was involved in an endeavor, it had to be a sure thing.

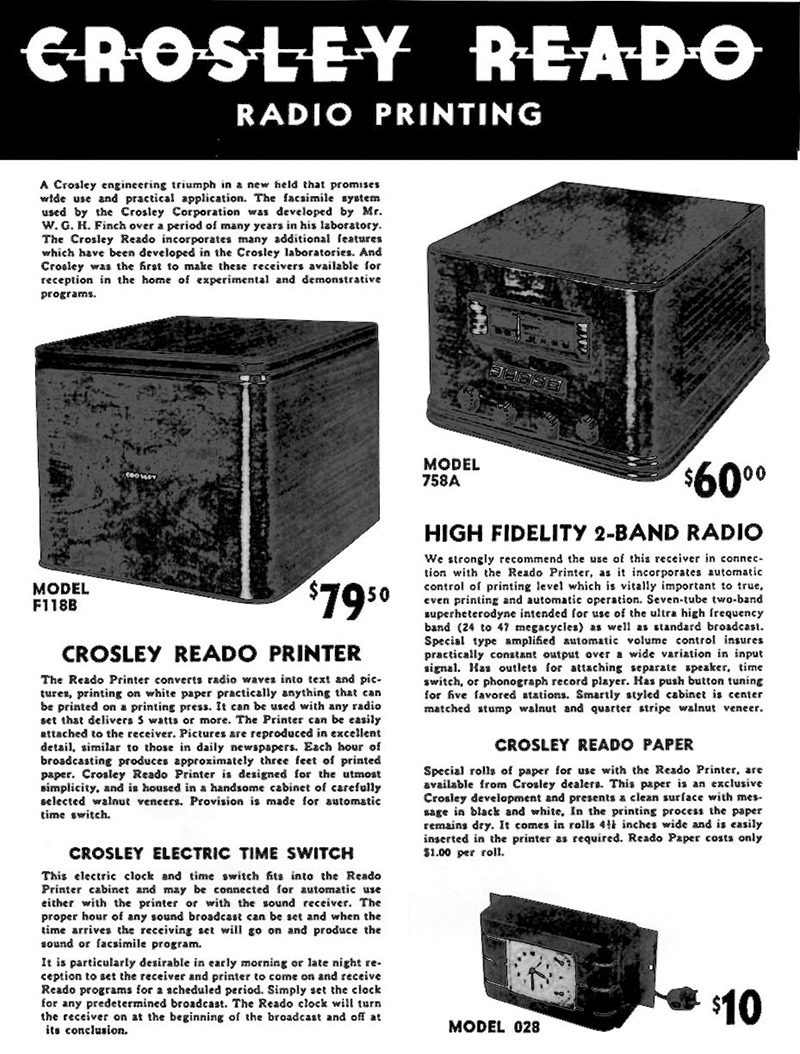

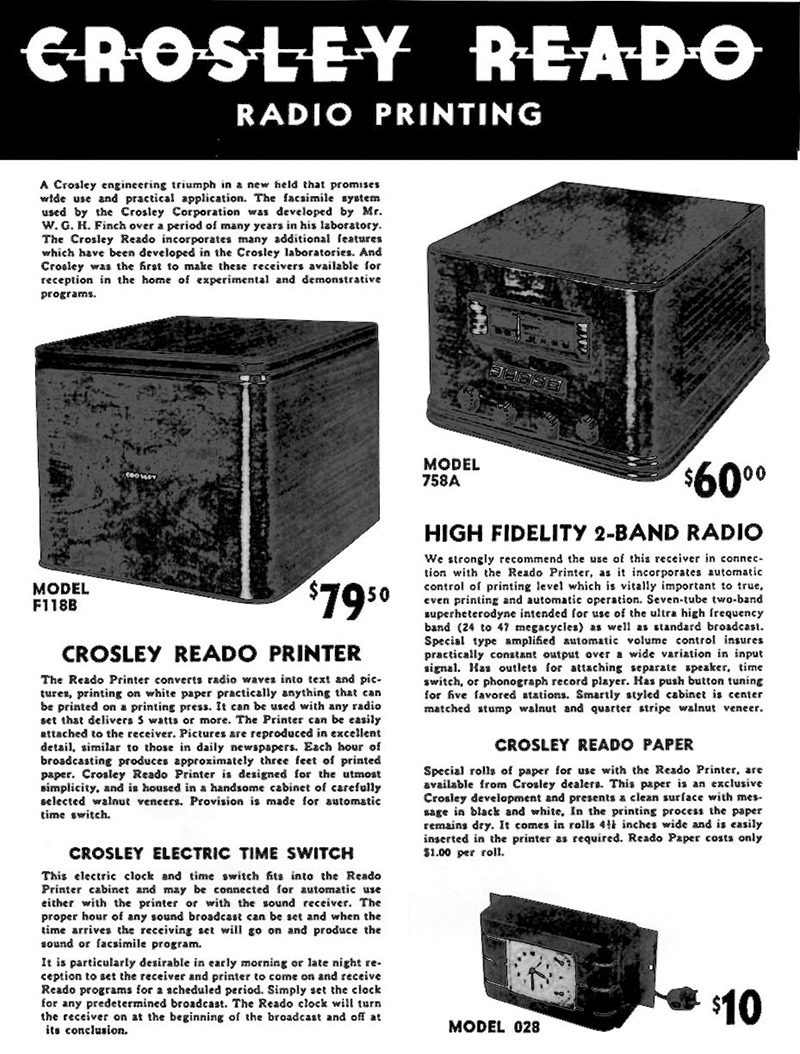

As was typical of any Crosley product, there were certain distinctive touches to Reado. Beginning with his first radio sets in 1922, Powel Crosley, Jr., always tried to beat the market with lower price sets. Reado was no exception. Printers were set to retail at $79.50, and designed to work with any radio. For $10.00 more, you could have an optional electric timer to turn the system on and off at preset times. A radio in a matching cabinet was also available for an additional $60.00.

FIGURE 5. The Crosley “Reado” radio facsimile system was sold in component form. The main unit — the printer — was also the most expensive, but could be used with any radio. For those for whom decor was important, there was a matching radio. A $10.00 timer rounded out the system (convenient if you went to bed early).

The man who found that he could use his decorative speaker housings to make decorative electric fans (thus saving money on design and component costs) found a similar way to reduce the production cost on Reados. The Reado printer was designed to fit into a Crosley radio cabinet, and to be compatible with any radio set. This meant that Reado customers didn't have to buy the radio and the printer together. It also meant that a certain Crosley radio model just happened to match the Reado's "… handsome cabinet, made of carefully-selected walnut veneers." This Crosley model was, of course, recommended for those wanting optimum performance.

Crosley was noted for including something innovative in products he made, whether it was a radio, car, airplane, or radio FAX receiver. In the case of Reado, Crosley developed an improved heat-sensitive paper that delivered crisp images on white paper. Also enhancing image quality was the fact that Reado machines printed a little slower than the Finch receivers — three feet per hour, rather than five.

All of this meant that radio FAX users everywhere would be assured of a better-performing product at a lower price — a Crosley hallmark.

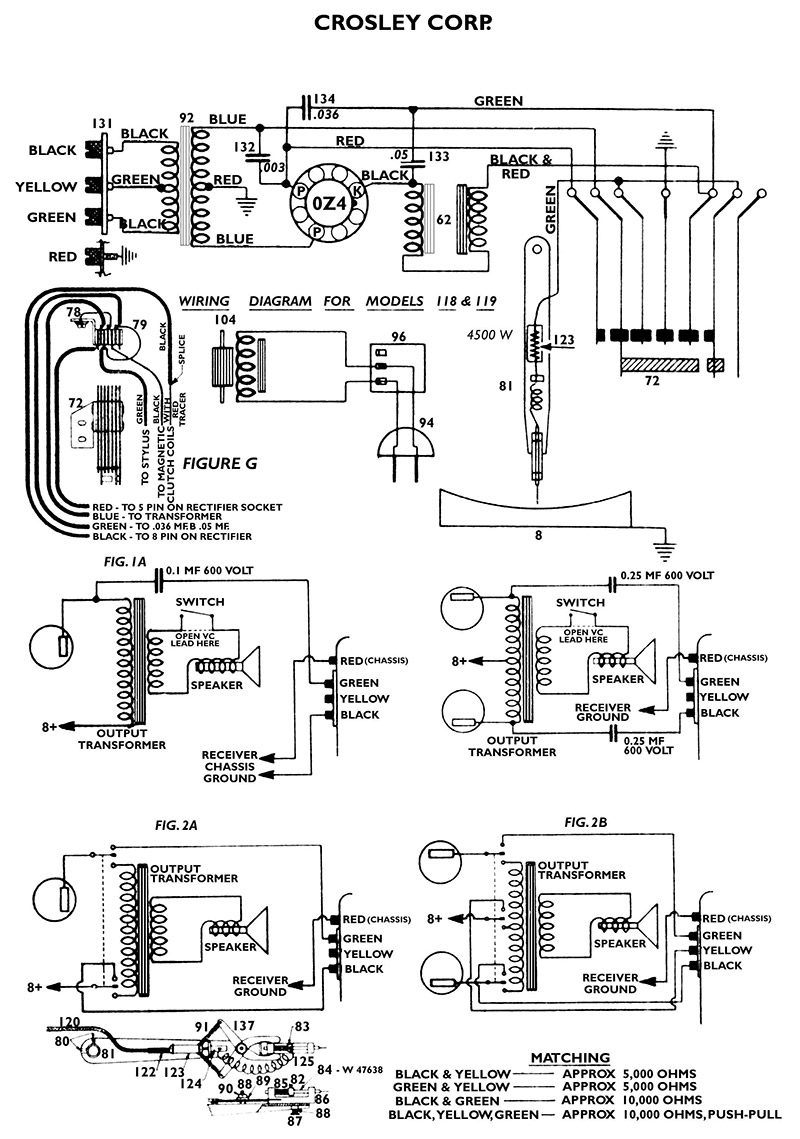

FIGURE 6. Wiring diagram for the Crosley 'Reado' readio printer.

With the factory in production, Crosley launched a complete business and marketing plan for the receivers and the broadcast service. In January 1939, he placed large ads for "Reado Radio Printing" in Cincinnati newspapers. Each ran from top to bottom of the newspaper page, and was close to the width of a Reado printout, more or less serving as a sample of the product.

The public was invited to daily demonstrations of the system from January 14 through January 24. The venue was the swank Hotel Gibson on Fourth Street in the center of Cincinnati. Although the newspaper ads noted that Reado units were "Sold for experimental use only," it was clear that this was a serious consumer product.

To round things out, the Crosley Reado was advertised with a clever motto: "Radio for the Eyes as well as the Ears." Radio facsimile printing was even demonstrated in the Crosley building at the 1939 New York World's Fair, alongside the Crosley Shelvador refrigerator and other appliances, radios, cameras, and the new Crosley automobile. All hosted by the Crosley Glamortone Gals, of course.

It appeared that the delivery of newspapers by radio broadcast was ready to roll, and that Crosley would be the leader in manufacturing the receivers. But fate conspired against Crosley, as well as Finch, RCA, and all the broadcasters who had invested so much in the radio facsimile system. Money was still tight in the late 1930s, and consumer response was less than overwhelming. This made advertisers leery of the new medium. Without strong advertiser support and subscriptions, the service was doomed. By 1940, radio facsimile newspaper delivery had ended.

The system might have been resurrected after World War II. By then, however, television was making its way into the nation's living rooms. Text and pictures by radio just couldn't compete with television's moving pictures and sound.

Still, William Finch hadn't lost his confidence in FAX as a mass communications medium, however. Right after World War II, he devised a new approach to transmitting newspapers. He intended to FAX them over telephone lines into the homes of millions of paying Americans.

Interestingly, his business plan included local and regional versions of the facsimile newspapers, plus one "super-newspaper" for national consumption. (Shades of USA Today!)

That didn't go over, either. Television and radio were more convenient, and people apparently preferred their newspapers on newsprint. Finch's company went bankrupt in 1952. (Fortunately, he was able to license some of this technology to RCA over the next few years.)

There's little left of radio facsimile-printed newspapers today, save for the odd receiver/printer in a radio collection or antique shop. In the 1940s and 1950s, radio amateurs used modified receiver/printers to pick up broadcasts of FAX weather reports to ships, but there really wasn't much use for them, otherwise. That's probably just as well. Even if radio-printed newspapers hadn't been killed by television, it would never have survived the Internet. NV