Back in March 1998, Time Magazine named David Sarnoff to its “Time 100” list of the most influential people of the 20th century.

In 1939, David Sarnoff told a crowd of curious viewers, “Now we add sight to sound.” Sarnoff went on to say, “It is with a feeling of humbleness that I come to this moment of announcing the birth in this country of a new art so important in its implications that it is bound to affect all society. It is an art which shines like a torch of hope in the troubled world. It is a creative force which we must learn to utilize for the benefit of all mankind. This miracle of engineering skill which one day will bring the world to the home also brings a new American industry to serve man’s material welfare ... [Television] will become an important factor in American economic life.”

And how. On that fateful day in 1939, with America recovering from its greatest depression and war rumbling in the distance, Sarnoff gave the world a look into a new life. Not only was he instrumental in creating both radio and television as we know them, he was also nearly clairvoyant in seeing how each medium would develop. He regarded black-and-white TV as only a transitional phase to color and even predicted the invention of the VCR. His stubborn pursuit of technology turned his employer, Radio Corp. of America, into a powerhouse in less than a decade.

From Minsk, Russia To Marconi Wireless

Before television, Sarnoff had to create a radio network. And, not surprisingly, its formation was a circuitous route. Like many inventors, Sarnoff came from remarkably humble beginnings. Born in 1891 near Minsk, Russia, to a poor Jewish family, he immigrated with most of his family to New York City in 1900. In 1906, Sarnoff was working as an office boy in the Commercial Cable Company, which had strung transatlantic telegraph cables from Ireland to Nova Scotia, and onward to Manhattan. That September, when a superior refused Sarnoff unpaid leave for the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah, he moved to another communications-oriented business, joining the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America.

At Marconi, Sarnoff truly found a home, and would rise from office boy to commercial manager. During the 1910s, he installed wireless telegraph equipment on ships, on the Lackawanna Railroad, and even in the Wannamaker Department store in Manhattan.

His experience with wireless telegraphy led to his most important achievement at Marconi. Sarnoff would take radio out of the exclusive province of the transportation industry and embryonic ham radio hobbyists, and put it into every American home. There it would share space with the other appliances that the inventors of the early 20th century were delivering to increasing numbers of consumers.

Music Via Wireless — And a Network

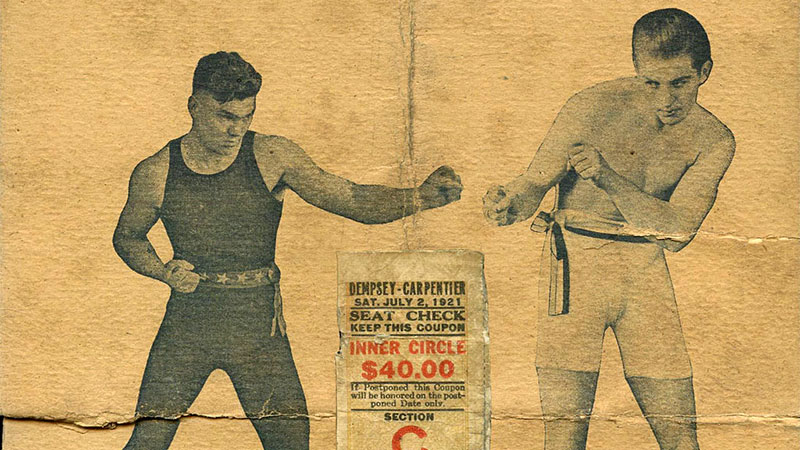

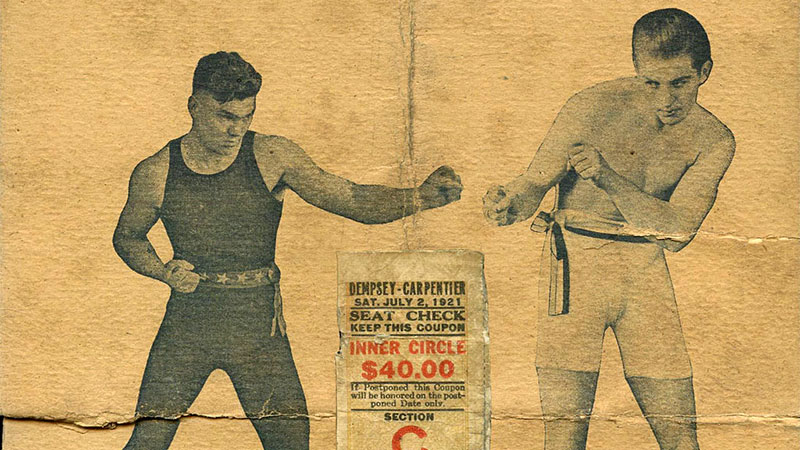

In a memo, Sarnoff wrote “The idea is to bring music into the house by wireless.” To do that, he needed a reason for people to buy these devices — in other words, programming. The classic radio shows our parents or grandparents told us about — starring early NBC celebrities such as Al Jolson, Jack Benny, and Bob Hope — all began with this decision. As did today’s ESPN, Monday Night Football, and ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Sarnoff’s first program? A 1921 Jack Dempsey-George Carpentier boxing match.

Its audience was a remarkable 300,000 listeners; the demand for radio took off exponentially from there. By the start of the 1920s, General Electric had formed Radio Corporation of America to buy out Marconi — and Sarnoff.

Sarnoff’s early radios weren’t cheap. His first product for RCA — the Radiola — sold for $75 (the equivalent of almost $1,000 in today's dollars) which illustrates both how inflation has dramatically increased prices. But it also demonstrates equally dramatically how the cost of technology has fallen. Today, anyone can purchase an AM radio. Despite its steep initial price tag, radio was an immediate hit, leading to sales of $83.5 million in 1924. (That's approximately $1,066,000,000 today.)

The stars that dominated radio were centered — as they are today — in New York (thanks to Broadway) and Hollywood (thanks to the movies). But even the strongest radio signal has its limits. To get programming into the hands of consumers nationwide (and sell more radios), Sarnoff knew he’d need to build a network of radio stations across the country. Or, as he dubbed it, the National Broadcasting Corporation, still going strong today as NBC. Like the other nascent radio networks that would form in its wake, it would make the jump to television in the late 1940s.

Radio, television, and NBC would eventually make Sarnoff an incredibly wealthy man, and quite rightly so. After leading NBC (and RCA) into the color television era in the 1960s, Sarnoff retired from RCA in 1970, and died the following year, at age 79.

The Life and Death of Mass Media

Like Time’s own Henry Luce, Sarnoff was one of the pioneers of the era of mass communications, transforming America from a nation of local newspapers and pamphleteers into an era where brute technological force allowed a handful of networks of, first, radio stations to flourish, and then television, to create a near-uniform electronic mass media.

That era had its drawbacks, of course. When critics of the 1950s decry the seeming uniformity of “the man in the gray flannel suit” and his Donna Reed-styled housewife, they rarely note how much the limitations of communications technology played in creating that uniformity. In contrast, it’s no coincidence that today’s era of extreme cultural diversity coincides with the fracturing of the mass media by the rise of “The Long Tail” of the modern info-stream: thousands of narrowly focused magazines, hundreds of television channels, and millions of websites.

So, what of AM radio, which Sarnoff wildly popularized? After a century that has seen the rise of motion pictures, radio, television, the Internet, and other media, we now know that no media fully destroys another. While most believed that the one-two punch of first television and then FM radio would bulldoze AM into obsolescence, it didn’t quite happen, did it? Just ask Rush Limbaugh, Howard Stern, and the other talkers making their own fortunes from a technology that David Sarnoff popularized nearly a century ago and is still going strong. NV