It was 1923, and radio was the phenomenon of the day. Over 600 broadcast stations were on the air, and Americans bought 100,000 receivers that year. (Sales would jump to 1,500,000 in 1924.)

This new instant mass medium flashed news of important events around the country in minutes instead of days. In addition to news, tens of thousands tuned in to hear music and learn from lecturers holding forth on their areas of expertise. A few tried to make sense of broadcast guitar or swimming lessons.

Those without radios gathered in taverns and restaurants to listen to election returns and descriptions of baseball games.

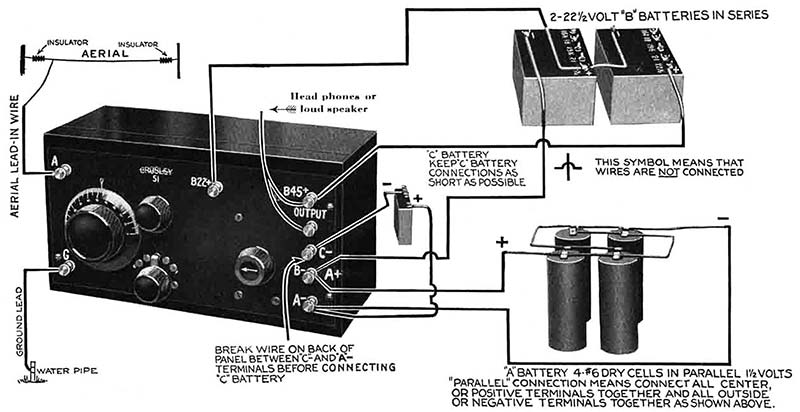

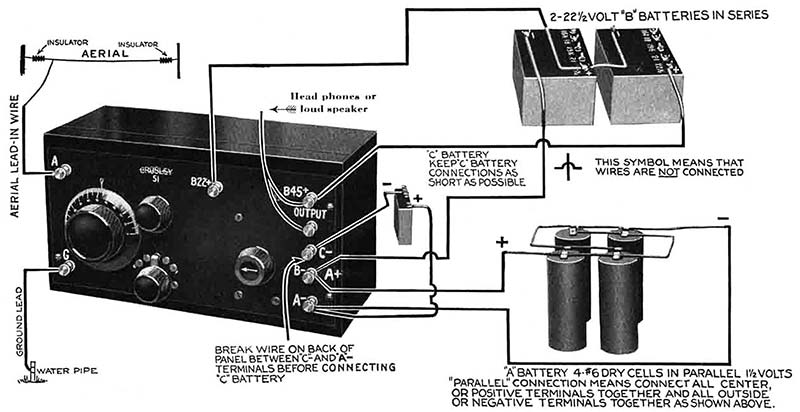

Typical components and hookup for a radio receiver in 1923.

New radio owners everywhere strung wire across their rooftops to make aerials, and then puzzled out how to connect a loudspeaker to the set, along with the A, B, and C batteries the setup required. (Soon enough, “house-current” radios would come along; most of the early ones were designed to draw power from fittings screwed into lamp sockets.)

Once the radios were set up, many owners hosted “radio parties” and danced to the latest jazz music with their friends.

At the same time, the game of Bridge was sweeping the country. It had been brought to New York from England in 1893. Here, as across the Atlantic, Bridge replaced the popular game of Whist as a top pastime, and quickly spread across the nation.

Whist is the direct forerunner of Bridge and is of English origin. Before the days of auction Bridge and contract Bridge, it was a very popular game, but these days, Whist has been superseded by Bridge.

Whist is a trick-taking card game developed in England. The English national card game has passed through many phases of development, being first recorded as Trump (1529), then Ruff, Ruff and Honours, Whisk and Swabbers, Whisk, and finally Whist in the 18th century.

In the 19th century, Whist became the premier intellectual card game of the Western world, but Bridge superseded it in this position by about 1900. Partnership Whist, with four players in two partnerships, remains popular in Britain in the form of social and fund-raising events referred to as Whist drives.

By the early 1920s, there were magazines and books devoted to Bridge. Regional, national, and international tournaments received extensive newspaper publicity. From the print coverage sprang Bridge authorities and even superstar players. Bridge was big business.

It was natural when, late in 1922, it occurred to someone in the marketing department of the United States Playing Card Company — then and now the world’s largest producer of playing cards — that radio might be used to promote Bridge, along with the Bridge decks and books published by the company.

A deck of Bridge cards. These were 1/4” narrower than conventional playing cards.

Such promotion would not be through radio advertising, however. On-air advertising was all but non-existent in 1923. The Department of Commerce (which at the time regulated radio) had yet to develop guidelines for advertising, and it was generally accepted by broadcasters that commercial use of the airwaves was prohibited.

A good many radio stations were operated by radio manufacturers, as a means of stimulating sales. Radio retailers, churches, newspapers, universities, hotels, and even Sears and Henry Ford owned radio stations. None sold advertising, although station owner’s products or causes were mentioned frequently, and this justified the cost of building and maintaining a station.

This being the situation, US Playing Card decided to start its own station, and thus combine the immensely popular game of Bridge with the radio phenomenon. The company purchased a parcel of land on high ground in Mason, OH (about 40 miles northeast of Cincinnati) and applied for a broadcasting license. The purpose would be to broadcast programs that promoted the game of Bridge in general and US Playing Card products in particular.

US Playing Card was assigned the call letters WSAI and the AM frequency of 970 kilocycles. This frequency was also occupied by Cincinnati’s largest station, WLW, so the two stations would have to divide up the time used. This was not uncommon in the early 1920s, because the Department of Commerce had allocated very few frequencies in the AM band for commercial broadcasting.

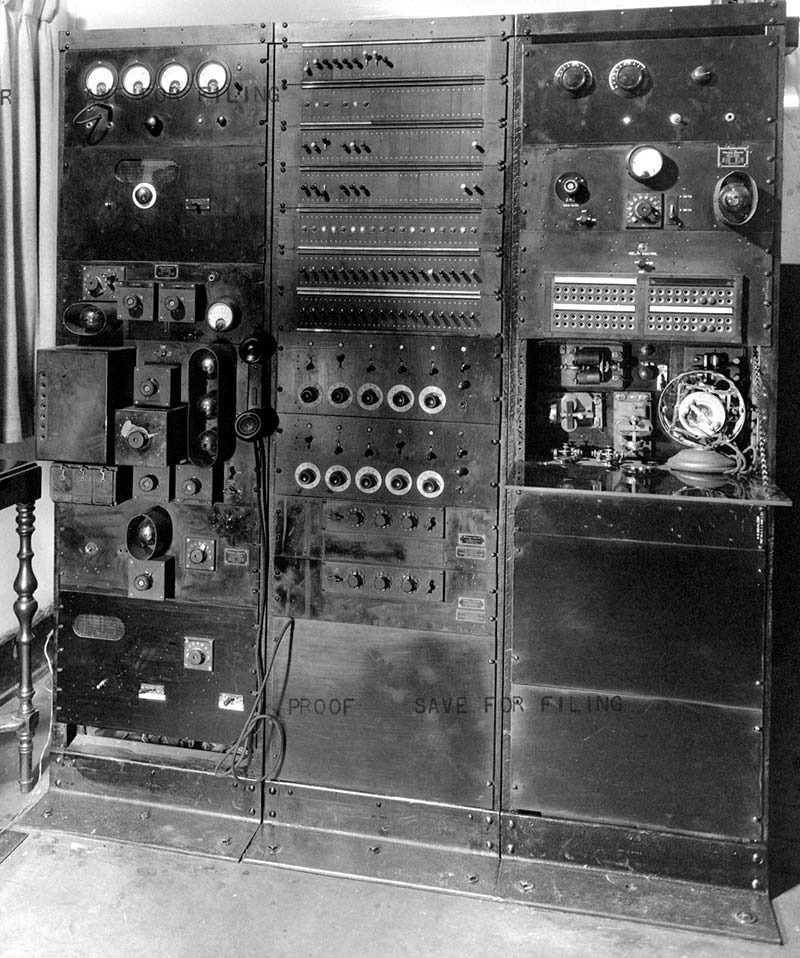

Deciding to go first-class all the way, the company constructed a modern building on its transmitter site, along with twin 250 foot towers to support the broadcast antenna. The very latest thing in radio transmitters was ordered: a 500 watt Western Electric Model 101A. This put WSAI at the leading edge of radio technology and would be sufficient enough to send WSAI’s signal across most of North America (there being little interference from other stations). The station’s studio was located in the US Playing Card’s headquarters building.

By coincidence, WLW had ordered the same transmitter from Western Electric to install in a new remote-controlled broadcast station to the west of Cincinnati. WLW’s parent company, Crosley, manufactured radios. The station went on the air to give buyers a reason to buy radios, as so many radio makers did back then. Its initial focus was on classical music and “educational lectures.”

The two transmitters arrived in Cincinnati in the same railroad car in March 1923, inspiring a good-natured race to see which station would get its transmitter on the air first. WLW won, going on the air in April. WSAI engineers put its transmitter on the air in June.

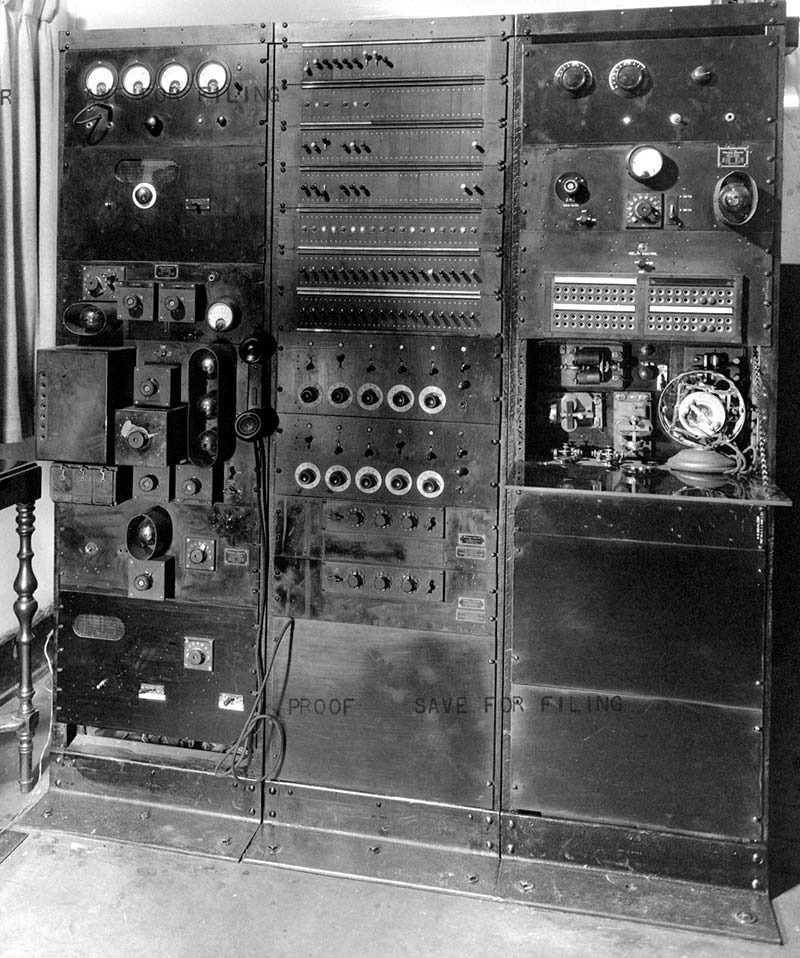

The 500 watt (yes, 500 watts!) transmitter that WSAI went on the air with in April 1923. The transmitter was built by Western Electric.

WSAI offered listeners Bridge lessons, talks about Bridge strategy, reports on tournaments, and much more — including a daily series of Bridge games. Noted players such as Sidney S. Lenz, Ella G. Pimm, Milton Work, and E.V. Shepard would play sets of games, narrating as they played. Advance announcement of the hands dealt the players were given on-air. The quality of the US Playing Card Bridge decks they used was mentioned frequently.

However, there were few hardcore mavens who would tune in to nothing but Bridge games and talks, so WSAI provided other entertainment. Listeners enjoyed the Toadstool Orchestra and the Bicycle Male Quartet (“Bicycle” being a company brand), along with news and “Midnight Entertainers.”

A unique element of WSAI’s programming was a carillon with 12 bells, built in 1924. According to the company, this was the first set of chimes built for radio broadcasting. The bells were designed and cast by the Meneely Bell Company of Troy, NY. The instrument was housed in a four-story tower of neo-Romanesque design, added to the four-story US Playing Card building at its main entrance.

The tower housed bells from 18 inches to 5-1/2 feet in diameter. A clock was included, with a face on each of the tower’s four sides. Music from the carillon was a hallmark of WSAI programming. All of this was underwritten by the increasing sales the company enjoyed as the result of its Bridge broadcasts.

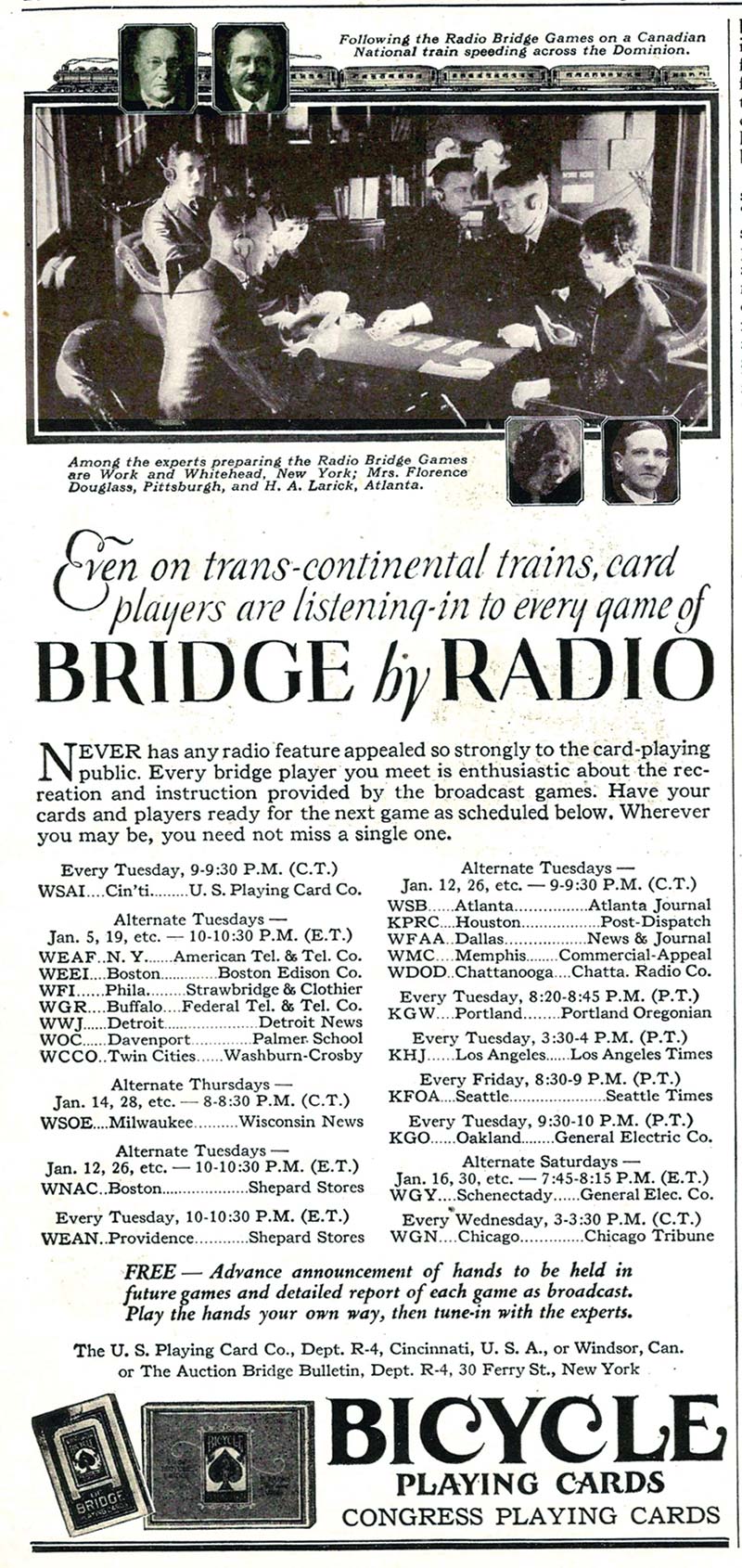

Late in 1926, the very first radio network — the National Broadcasting Company’s NBC network — was established, with WSAI among the founding members. WSAI began sending its Bridge programming out through NBC’s “Red” network to stations in Boston, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Detroit, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and other major US cities. Thanks to the network, people listened to radio not only in their homes, but also in shops and other commercial establishments. It was possible to listen to WSAI on radio-equipped passenger trains as well.

WSAI was heard not only in most of the United States, but also as far away as New Zealand at night, thanks to the “skywave” phenomenon and to the station’s excellent transmitter and tower location. It helped that no other station used the same frequency as WSAI, except for WLW which was not on the air when WSAI was broadcasting.

Obviously, US Playing Card spent a considerable amount of money establishing and maintaining WSAI. In addition to the initial cost — which ran well into five figures — the company had to hire technical and creative staff. The cost of electricity and special telephone lines required to send studio programming to the transmitter ran into several thousand dollars per month. However, the impact on US Playing Card’s sales was enormous.

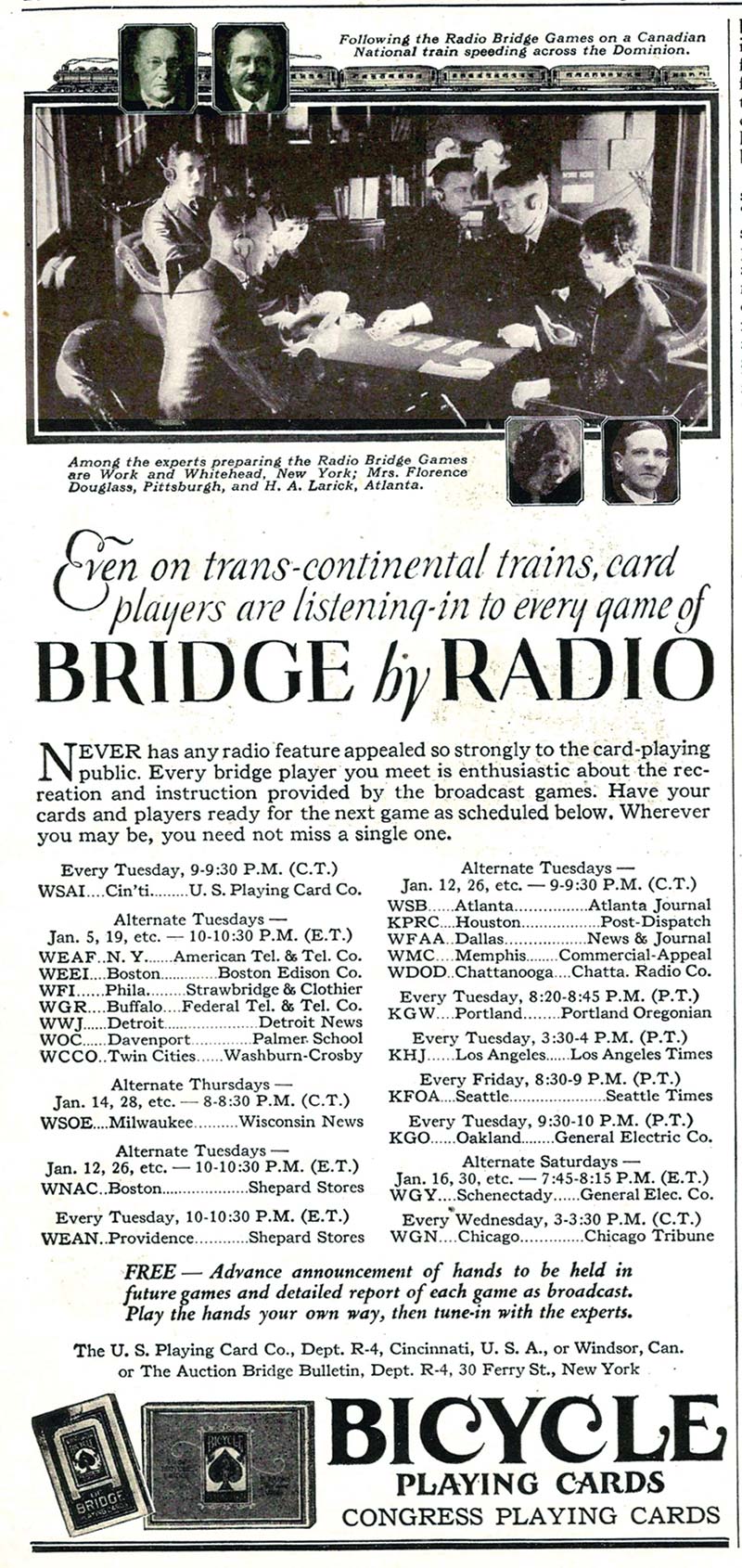

US Playing Card supported the Bridge broadcasts with extensive magazine advertising, providing radio schedules for all the cities where the games could be heard. To build customer enthusiasm and measure the effectiveness of the broadcasts, the company encouraged listeners to write in for printed reports of each game. Also available were advance listings of the hands to be played in future games, so listeners could play the hands their way, then compare their play with that of the experts.

An ad in “American Magazine” detailing WSAI’s Bridge programming, with station listing and schedule.

Increased sales of card decks and other merchandise, outside advertising, and revenue received for network feeds more than paid for WSAI’s broadcasts for several years. By 1928, however, US Playing Card was beginning to feel burdened by the station. It was, after all, in the business of manufacturing playing cards, books, score sheets, and other gaming accoutrements. Moreover, the transmitter, tower, and studio (located in US Playing Card’s main office building in Cincinnati) wasn’t really needed; Bridge games could originate and be transmitted from any NBC network station’s facilities. Plus, national advertising over NBC was less expensive than WSAI’s operating costs.

WSAI’s reach extended into Canada, so radio Bridge was promoted to listeners there as well as in the US. WSAI’s Bridge stars played on a radio-equipped Canadian National Railways passenger train.

US Playing Card executives made the decision to get out of the radio business. The company’s attorney informally suggested to the owner of the largest radio station in Cincinnati, WLW, that WSAI might be for sale. Negotiations were opened and US Playing Card quickly reached an agreement to sell WSAI to WLW.

Today, WSAI can be found at 1360 on the AM dial. Its 5,000 watt transmitter limits its coverage to the “tri-state” area where Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky come together at Cincinnati.

WSAI’s current format is “sports/talk” (it’s a Fox Sports affiliate). Few of its listeners are aware that WSAI was once “the voice of Bridge.” NV

The United States Playing Card Company

www.usplayingcard.com

WSAI (Fox Sports Radio)

https://foxsports1360.iheart.com